Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) Awareness Month

If you suffer from the following ongoing symptoms, you might have IBS:

· Abdominal Pain

· Bloating

· Constipation

· Diarrhea

IBS is a chronic, often debilitating, functional gastrointestinal disorder with symptoms that include abdominal pain, bloating, and altered bowel behaviours. These are constipation and/or diarrhea, or alternating between the two stool consistency extremes. IBS is a functional disorder, in that the function or movement of the bowel is not quite right. There are no medical tests to confirm or rule out a diagnosis and yet it is the most common gastrointestinal condition worldwide and the most common disorder presented by patients consulting a gastrointestinal specialist (gastroenterologist).

IBS affects an estimated 13-20% of Canadians at any given time, depending on which criteria researchers use to assess symptoms. The lifetime risk for a Canadian to develop IBS is 30%.

IBS can begin in childhood, adolescence, or adulthood and can resolve unexpectedly for periods throughout an individual’s lifespan, recurring at any age. In Canada and most Western nations, IBS seems to arise significantly more frequently in women than in men, but the reason for this remains unclear.

Although each person can have a unique IBS experience within the range of known symptoms, this condition typically decreases a person’s quality of life. Interestingly, only about 40% of those who have IBS symptoms seek help from a physician.

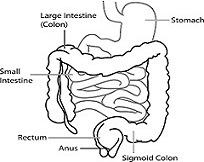

Over the years, some have called this collection of symptoms by many names, including mucous colitis, nervous colon, spastic colon, and irritable colon, but these are all misleading, mostly because IBS is not limited to the large intestine (colon). Sometimes, IBS is confused with colitis or other inflammatory diseases of the intestinal tract, but the difference is clear – in IBS, inflammation or infection is not evident.

Almost every human being has experienced abdominal cramping, bloating, constipation, or diarrhea at some point in his or her life. However, those who have IBS experience these multiple symptoms more frequently and intensely, to the extent that they interfere with day-to-day living.

A person who has IBS is likely to have a sensitive digestive system with heightened reactivity, so that the bowel responds quite differently to normal gut stimuli, such as the passage of solids, gas, and fluid through the intestines. These unusual movements may result in difficulty passing stool, or sudden, urgent elimination. Up to 20% of those who have IBS report untimely passage of stool. Some individuals with IBS may also experience straining to pass stool along with a feeling of incomplete evacuation (tenesmus) and immense relief of pain/discomfort when gas finally passes. A stringy substance (mucous) may cover the stool.

Individuals could have different combinations of symptoms, with one being predominant, while others have more random and unpredictable digestive symptoms. These altering bowel experiences and their unpredictability can lead to a high degree of anxiety for the IBS patient. Stool consistency may vary enormously, ranging from entirely liquid to so firm and separated that it resembles small pebbles. External factors, such as stress, can affect stool consistency. IBS is often broken down into different sub-groups, which are associated with stool consistency.

· IBS-D is when the digestive system contracts quickly, transiting products of digestion rapidly through the digestive tract, resulting in frequent, watery bowel movements (diarrhea).

· IBS-C is when the digestive system contracts slowly, delaying transit time for products of digestion, resulting in hard, difficult to pass, infrequent stools (constipation).

· IBS-M is when the transit time throughout the digestive tract fluctuates, causing patients to experience a mix of both diarrhea and constipation, often alternating between the two. These extreme stool consistencies can sometimes even occur within the same bowel movement.

Intestinal pain can result as material in one section of the gut passes through slowly while material in another section passes through quickly. These actions, occurring simultaneously, can result in alternating between constipation and diarrhea, sometimes within the same bowel movement. In addition, prolonged contractions of the bowel might prevent the normal passage of air, triggering bloating, belching, and flatulence. Bloating could become so severe that clothing feels tighter and abdominal swelling becomes visible to others.

Pain manifests in many ways with IBS. It can be ongoing or episodic, come on sharply and then resolve rapidly, occur occasionally or frequently, and move from one location in the bowel to another very quickly. Digestive pain often occurs following a meal and can last for hours. Those who have IBS tend to have a quicker and more intense reaction to digestive tract pain stimuli than do those who do not have IBS.

Other Experiences

Symptoms occurring outside of the digestive tract, possibly related to IBS, can include sleep disturbances, fibromyalgia, back pain, chronic pelvic pain, interstitial cystitis, temporomandibular joint disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, and migraine headaches. Female patients who have IBS have also reported discomfort during sexual intercourse (dyspareunia).

Patients who have IBS-D or IBS-M often feel unable to engage in work or social activities away from home unless they are certain that there are easily and quickly accessible bathroom facilities available. Patients with IBS-C are often in such pain that they find even slight body movements uncomfortable. Pain and frequent bowel movements or preoccupation with an inability to eliminate stool may make school, work, and social situations difficult.

Those who suffer with IBS might experience some psychological symptoms. These include a diversity of strong emotions related to the condition that range in intensity, including anxiety, depression, loss of self-esteem, shame, fear, self-blame, guilt, and anger. Fortunately, psychological management of IBS can often help reduce these symptoms.

Diagnosis

As the symptoms of IBS are varied and there are no organic tests to determine specifically whether a patient has IBS, part of the diagnostic process is to rule out other known diseases. Typically, a physician takes the following steps to reach an IBS diagnosis.

Medical History: A physician reviews the patient’s medical history, considering bowel function pattern, the nature and onset of symptoms, the presence or absence of other symptoms, and warning signs that might indicate some other diagnosis. It is important to note what symptoms do not relate to IBS and these include weight loss, blood in the stool, and fever. If the need to defecate wakes you from your sleep, you should report this to your physician as it is not typical of IBS and could have other implications.

Bowel pain and uterine/ovarian pain may be difficult to distinguish from each other, so gynecological conditions might delay or confound an IBS diagnosis in women.

Physical Examination: During a physical evaluation, the bowel may have involuntary jerky muscular contractions (spastic) and seem tender, although the patient’s physical health usually appears normal in other respects.

The physician may also request routine blood and stool tests to rule out known organic diseases. Some symptoms of celiac disease overlap those of IBS, so a family history of this disease might be a reason to test for it.

A physician makes a diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome after taking these steps, and after considering the nature of the patient’s symptoms in relation to the information detailed in the Thirty-Second IBS Test.

Possible Causes

The cause of IBS has not been determined. It primarily presents as a functional disorder with altered patterns of intestinal muscle contractions. While IBS is chronic and painful, there is no evidence for a relationship between this disorder and an increased risk of more serious bowel conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease or colorectal cancer.

Although not proven, theories exist as to factors that influence IBS symptoms, including:

· Neurological hyper-sensitivity within the gastrointestinal (enteric) nerves

· Physical and/or emotional stress

· Dietary issues such as food allergies or sensitivities, or poor eating patterns

· Antibiotic use

· Gastrointestinal infection

· Bile acid malabsorption

· The amount or pattern of physical exercise

· Chronic alcohol abuse

· Abnormalities in gastrointestinal secretions and/or digestive muscle contractions (peristalsis)

· Acute infection or inflammation of the intestine (enteritis), such as traveller’s diarrhea, which may precede onset of IBS symptoms

The gastrointestinal (GI) system is very sensitive to the hormone released when one is excited, fearful, or anxious (adrenaline) and to other hormones as well. Changes to female hormone levels also affect the GI tract, so IBS symptoms may worsen at specific times throughout the menstrual cycle. Since hormones play a role in the transit time of food through the digestive tract, this might account for the predominance of IBS in women, although the evidence is still lacking.

It is important to note that since there is no definitive proof of the source of IBS, many promoted potential ‘causes’ and advertised ‘cures’ of this syndrome are simply speculation.

Management

The gastrointestinal tract is an extremely complex system, influenced by many nerves and hormones. It is clear that both the secretions and motility of the intestine are affected by the type of food eaten, the frequency and environment of eating, and by various medications.

The most important aspect of IBS treatment is for patients to understand the nature of their unique symptoms and any potential aggravating or triggering factors. Also helpful is recognizing that it may take time before bowel function returns to a more normal state.

Dietary and Lifestyle Modifications

The bowel responds to how and when a person eats, so it’s important to eat regular, well-balanced, moderately sized meals rather than erratic, variable meals. Occasionally, IBS symptoms improve by allowing sufficient time for regular eating and bathroom routines.

Some IBS patients report that dietary fats trigger symptoms, as can the food additive MSG (monosodium glutamate). Some find symptoms worsen when consuming large quantities of liquids with meals. Others find that cooking vegetables and fruits lessens IBS symptoms, compared to when eating them raw. Particularly if the predominant symptom is diarrhea, an IBS patient should avoid or decrease consumption of gastrointestinal stimulants such as caffeine, nicotine, and alcohol.

IBS patients do not necessarily produce more gas than the non-IBS population, but their intestines may be extra sensitive to the passage of gas. Things that might help include reducing ingestion of swallowed air, which is the major source of intestinal gas, and avoiding large quantities of gas-producing foods. To decrease swallowed air, avoid gum chewing, gulping of food, washing food down with liquids, and sipping hot drinks.

Poor-fitting dentures, a chronic postnasal discharge, chronic pain, anxiety, or tension may also contribute to increased air swallowing. For more information, ask about our Intestinal Gas pamphlet.

Other IBS patients have found lower carbohydrate diets helpful. A proposed therapy for IBS, called the low FODMAP diet, is increasing in popularity in North America. FODMAP is an abbreviation for Fermentable Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides, and Polyols. These are the names of poorly digested carbohydrates, which travel into the large intestine where they are fermented by the resident bacteria. For many individuals, these foods do not cause any problems, but some who have IBS find that these foods worsen their symptoms. The diet involves not eating specific foods for 6 to 8 weeks to see if symptoms subside. If they do, then the person can slowly reintroduce FODMAPs into the diet to a tolerable limit. FODMAPs are in many foods so removing them from your diet can increase your risk of nutritional deficiencies. While the results of studies conducted on the low FODMAP diet suggest its promise as a possible management approach for some IBS patients, further research is required, and it does not help everyone.

SOSCuisine’s Low FODMAP for IBS Meal Plans are designed to help guide you during the elimination and food challenge phase of the Low FODMAP Diet. They allow for your symptoms to be reduced as much as possible, to ensure best possible results during the food challenge of individual FODMAP. SOSCuisine’s program also allows you to remove individual FODMAP from any of their meal plans once the ones that cause symptoms are identified, for a more personalized eating plan.

By keeping a food intake diary and noting any adverse reactions, you can quickly identify and remove problematic food from your diet and determine an approach that works best for you. Be sure to consult a registered dietitian before eliminating any food group long-term. For more information on food groups and a balanced diet, consult Canada’s Food Guide, available from Health Canada.

Fibre

An important step in controlling the symptoms of IBS is to increase dietary fibre from plants, which the human body cannot digest on its own. The fibre content of foods stays the same with cooking, although this process may change its effect within the gut. When considering fibre, it is important to look at both the fibre content of foods and the type of fibre (insoluble or soluble).

Gradually increase dietary fibre, allowing your body to adjust to the change, making sure to increase the amount of water you drink. This will minimize any adverse effects that may arise from a sudden dietary change. Your physician or dietitian may recommend the addition to your diet of one of the many commercially prepared, concentrated fibre compounds on the market, such as Benefibre®, or Metamucil®.

Insoluble fibres increase stool bulk, increase colonic muscle tone, and accelerate the transit

time of gastrointestinal contents, thus relieving mild constipation.

Water-insoluble fibres include:

· Lignin (found in vegetables)

· Cellulose (found in whole grains)

· Hemicellulose (found in cereals and vegetables)

Soluble fibres form gels when mixed with water, making the bowel contents more sticky and resistant to flow (viscous) so that food stays in the digestive tract longer. This is important for people who suffer from diarrhea.

Some examples of water-soluble fibres include:

· Pectins (e.g., apples, bananas, grapefruit, oranges, strawberries)

· Gums (e.g., cabbage, cauliflower, peas, potatoes, oats, barley, lentils, dried peas, beans)

It is important to note that for some IBS-D patients, a diet excessively high in bran fibre might trigger more frequent diarrhea, while other types of fibre could still be helpful. Consult your physician or dietitian if you have any questions regarding fibre in your diet.

Stress

Separate from the central nervous system, the gut has its own independent nervous system (enteric), which regulates the processes of digesting foods and eliminating solid waste. The enteric nervous system communicates with the central nervous system and they affect each other. Many IBS patients report high levels of stress, which might relate to factors such as poor sleep habits, working too hard, and the excessive use of caffeine, alcohol, and/or tobacco. IBS is not a psychological disorder, even though stress, depression, panic, or anxiety, may aggravate bowel symptoms. Proper exercise and rest can help reduce stress and positively influence IBS symptoms.

Psychological treatments may augment medical treatment, including relaxation training, time management, lifestyle changes, and cognitive restructuring.

Physiotherapy

The pelvic floor consists of muscles that help control defecation. IBS patients might have pelvic floor incoordination (dyssynergia/anismus). A physiotherapist with training in pelvic floor rehabilitation can conduct a thorough examination which may include a digital vaginal exam (for women), a digital rectal exam, observation and touching (palpation) of the perineum and abdominal wall, and electromyographic (EMG) biofeedback assessment. The goal of physiotherapy treatment is to develop the ability to relax the pelvic floor completely while simultaneously allowing gentle propulsive forces from deep abdominal muscles to evacuate the bowel fully. Physiotherapy might also help those who have diarrhea-predominant symptoms and experience bowel urgency and/or incontinence of watery stools. Check with your regional physiotherapy association to find a registered physiotherapist who has incontinence or pelvic floor training.

Click here to learn more about Irritable Bowel Syndrome

Source: Canadian Society of Intestinal Research